There have been a variety of cases over the last couple

weeks, but I will focus on a couple in this post.

Another case that we are currently working on involves a

horse that had a tail wrap applied too tight causing the tissue around the tail

to die. The referring vets tried to

remove the dead parts of the tail in addition to several vertebrae, but were

unable to close the wound fully.

Warning: The following images may be a bit graphic for some people.

The tail was very short on presentation to Brown Equine

Hospital. There was some dirt and

various topical antiseptic agents on the open wound so we clipped and cleaned

the tail and wound to better assess the injury

After cleaning, we could see the wound was a mixture of

necrotic (the black tissue) and granulation tissue (the bright red

tissue).

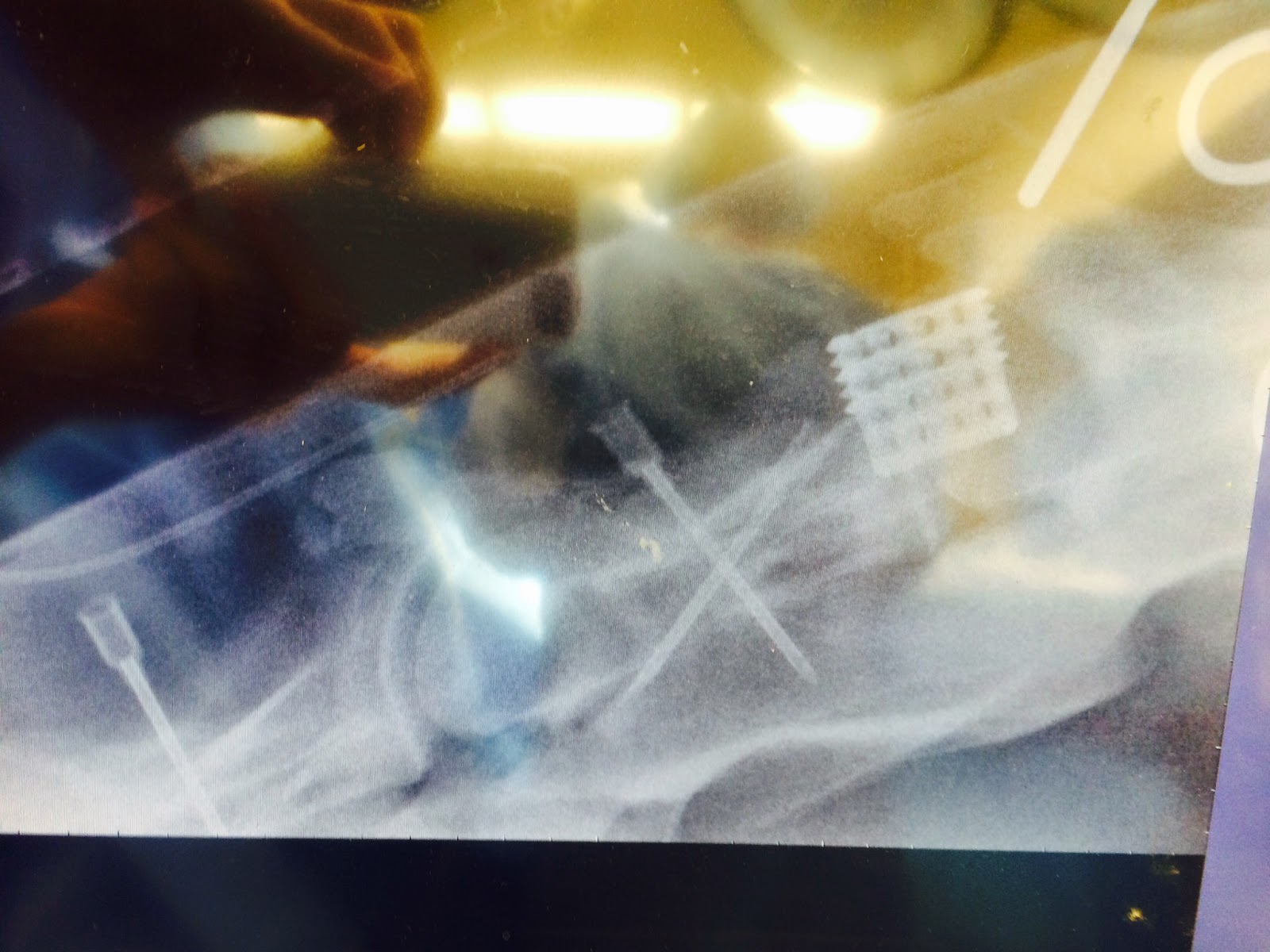

Dr. Hackett and Dr. Younkin removed the remainder of that

vertebrae and a great deal of the granulation tissue in order to have enough

skin to close over the end of the tail.

Closure with a Near-Far-Far-Near suture for tension relief, and then a simple interrupted pattern was placed in between the tension relieving sutures for apposition of the raw edges.

The patient will need to be on systemic antibiotics and

anti-inflammatory drugs for several days to prevent further infection and

minimize pain, but the prognosis for recovery is good!

The next couple weeks will bring several big changes to the

clinic. Dr. Younkin will be finishing

his internship at BEH and heading off to Kansas State for a new position. He has been a valuable source of information

in my first month at BEH and we wish him only the best as he advances in his

career. A new intern who recently

graduated from University of Pennsylvania will be starting next week, and BEH

will also be welcoming a new board certified surgeon to the team from Tufts University,

Dr. Patricia Provost. I am looking

forward to having even more people to learn from!

Until next week!

.jpg)